HOW COLUMBIA PICTURES CHANGED THE WORLD AT 24 FRAMES PER SECOND

In the fall of 1989, as Disney and Universal were prepping popcorn-friendly fare like Pretty Woman and Back to the Future Part III, a young Columbia Pictures creative exec took a meeting with a USC student possibly interested in a script-reader job.

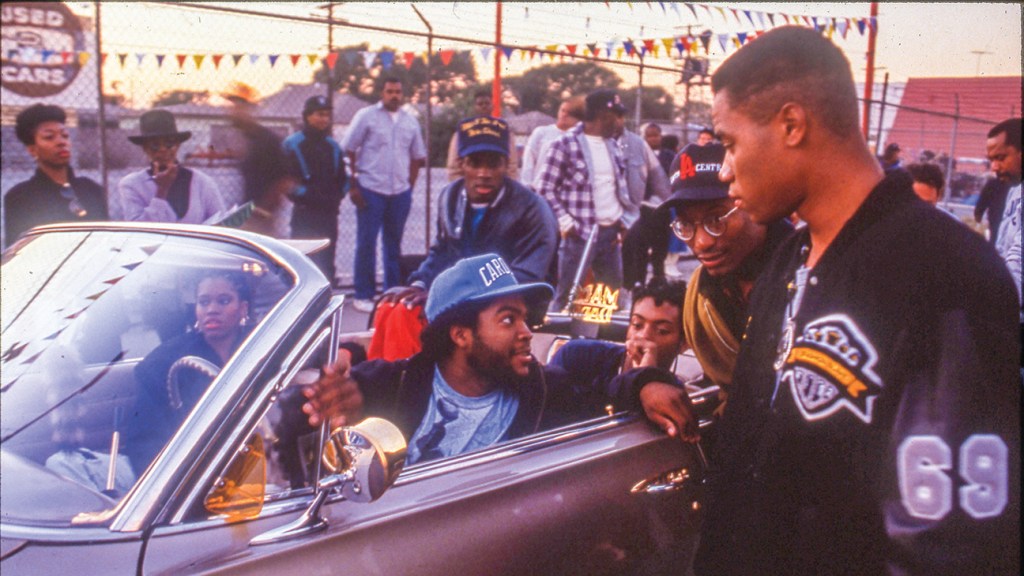

"John Singleton shows up to our offices in Burbank," recalls Stephanie Allain. "His confidence at 22 was eerie, but all he wanted to do is talk about his screenplay for Boyz n the Hood. I said, ‘OK, send me the script.' "

Two weeks later, after Allain read Singleton's saga about Black teenagers in South Central, she emerged from her office sobbing. "I thought, ‘This is my world.' I'd gone to school in Inglewood. I knew those kids. It felt like John had written it for me."

It's theoretically possible, of course, that any number of studios might have ended up greenlighting Singleton's gritty drama about growing up in the booming gang culture of one of L.A.'s toughest neighborhoods. But it's not likely. Because throughout much of its history, Columbia has been a studio that's made difficult, socially provocative material a cornerstone of its slates. Despite persistent corporate shuffles - or maybe because of them - the studio has carved out a well-deserved reputation for turning hot-button topics into hit entertainment. From 1967's Guess Who's Coming to Dinner (which featured the big screen's first interracial kiss) to 1979's The China Syndrome (which warned of the threat of nuclear power just weeks before the real-life Three Mile Island disaster) to 1979's Kramer vs. Kramer (the first major movie to tackle the touchy subject of divorce), Columbia has regularly taken on material that most other studios might consider box office poison.

Partly, that's thanks to gutsy executives like Allain, one of the few Black creatives at any studio back in the late 1980s. But it's also because early on, Columbia realized something that not many others in Hollywood figured out until much later: that in a crowded field, risk-taking can sometimes be the best, most profitable business plan.

"In Hollywood, risk is only ever deployed as a solution to a struggle," notes Stephen Galloway, dean of Chapman University's Dodge College of Film and Media Arts and author of the Laurence Olivier-Vivien Leigh biography Truly, Madly, as well as the forthcoming Hollywood 1939 (and a former THR editor). Columbia, he adds, was often pushed to lean into the zeitgeist because it didn't always have the resources to compete with the prestige IP of its flusher competitors. "As a result, Columbia made a lot of bold, innovative movies," he says.

That wasn't always the case. In the 1930s and '40s, Columbia was home to Frank Capra, whose rousing feel-good dramas like It Happened One Night and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington- dubbed by some as "Capra-corn"- all but defined the studio. It was where stars like Jean Arthur, Cary Grant and Rita Hayworth hung their hats, making scores of screwball comedies, and where the Three Stooges slapsticked through countless two-reel serials.

By the 1950s, however, like every studio, Columbia was struggling with dwindling theater attendance and the rise of a threatening new medium - television. Without the assets to greenlight big-budget extravaganzas like MGM's Ben-Hur or Paramount's The Ten Commandments, they instead lured audiences with somewhat more provocative fare, like From Here to Eternity (which included a less-than-patriotic portrait of the U.S. military as well as Burt Lancaster and Deborah Kerr engaging in a torrid adulterous make-out session on a Hawaiian beach) and On the Waterfront (in which a young actor named Marlon Brando portrayed a longshoreman entangled with corrupt union bosses).

A decade later, in the 1960s, Columbia was churning out edgy critical hits like Dr. Strangelove (Stanley Kubrick's comedy about the end of the world), eventually accruing enough clout to tackle what was then the ultimate taboo - interracial romance - in Stanley Kramer's drama Guess Who's Coming to Dinner. It centered on the daughter (Katharine Houghton) of a liberal San Francisco couple (Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn) who announces her intentions to marry a Black doctor (Sidney Poitier). The film had massive star power (Poitier had become the first Black man to win best actor just a few years earlier), but it nonetheless stirred dissension in Columbia's ranks.

According to the American Film Institute, the studio's East Coast executives felt the topic of interracial romance - more specifically, the optics of a white actress kissing a Black actor in a major motion picture - was too risky, given the cultural climate. (More than a dozen U.S. states still had laws criminalizing intimacy between people of different races.) Adding to these headaches were production delays due to Tracy's ill health and the studio's inability to insure him, so he and Hepburn agreed to lower their salaries to finish the film. (Tracy died shortly after filming ended.)

Snafus and controversies aside (the film was banned in many cities across the South), Guess Who's Coming to Dinner was practically prescient about the social changes looming just around the corner. It was shot just months before the Supreme Court's landmark 1967 Loving v. Virginia decision, which stated that prohibiting interracial marriage violated the Constitution. The movie earned nearly $57 million worldwide - the most of any Columbia release in history at the time - and 10 Oscar nominations, with wins for Hepburn and its screenplay.

Two years later, in 1969, Columbia released Easy Rider, the movie that turned the counterculture into popular culture. Made by and starring hippie icons Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda, the film's bombastic youthfulness (and raucous employment of rock music) reflected a society on the brink of revolt and launched an entire genre of youth-centric rebellious cinema.

"Hollywood's institutions were finally breaking down," says Peter Guber, who as Columbia's chief in the early 1970s racked up hits like the The Way We Were (in which Robert Redford and Barbra Streisand took on the previously taboo subject of the Hollywood blacklist). "It really felt like new voices were coming into the business," he says.

Voices, for instance, like Martin Scorsese, who pushed the envelope of urban blight and graphic violence with Taxi Driver, the film that introduced Jodie Foster as a 12-year-old prostitute - and ended up nominated for best picture. And it wasn't just new voices getting a hearing at Columbia in the '70s, but also totally new subject matters, like the dangers of nuclear power.

Originally, 1979's China Syndrome was going to star Richard Dreyfuss, fresh from his star-making turn in Close Encounters of the Third Kind, the alien epic Steven Spielberg had made for Columbia in 1977. When Dreyfuss pulled out, Columbia's then-vp production, Sherry Lansing, reimagined the project as a vehicle for Jane Fonda, who had long been a vocal opponent of nuclear energy. The studio had only one concern, Fonda recalls, which was that "people would think the movie was about China." Fonda herself wasn't worried. "I thought it was a really good thriller that could be an audience-pleaser, even if they didn't share our feelings about nuclear energy."

Twelve days after its release, Syndrome received a surreal PR bump: On March 28, 1979, there was a partial meltdown at the Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating Station near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. While no deaths were reported, scientists were mixed on the fallout and severity of the incident. But one clear result of the accident was that it sent audiences flocking to movie theaters; the film ended up earning nearly $52 million and four Oscar nominations. "It was a fortuitous coincidence, and a turning point for nuclear: No new plants were built after our movie," says Fonda, affirming data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration that reported 67 planned nuclear builds between 1979 and 1988 had been canceled.

If Syndrome demonstrated Columbia's knack for finding eerily timely subject matter, 1987's La Bamba proved it was ahead of its time regarding cultural inclusiveness. Based on the life of Chicano pop sensation Ritchie Valens (played by newcomer Lou Diamond Phillips, a half-Filipino actor discovered in Texas after some 600 others auditioned for the part in L.A. and New York), the film opened up an entire new, or at least entirely neglected, audience for Hollywood: Latin moviegoers. Leaning heavily into word-of-mouth buzz and near-constant radio play of the movie's theme song - a cover of "La Bamba" by the East L.A. band Los Lobos - and releasing a print of the film dubbed in Spanish in select markets (an all but unheard-of marketing maneuver in those days), Columbia's bet paid off big-time. Within six weeks, the movie had grossed over $37 million, including $2 million from the dubbed version.

"Our movie proved that Latinos go to the movies," says its director, Luis Valdez. "There just need to be more movies made by us, about us."

La Bamba's success no doubt gave Columbia some confidence when Singleton turned up for that job interview with Allain. Although Black audiences had been courted before, this was done mostly with blaxploitation pictures like Shaft and Super Fly. More serious major studio dramas about African American characters directed at African American audiences were still at that point somewhat rare. But Boyz wasn't delving into entirely unfamiliar waters. "Much like Easy Rider and Taxi Driver, Boyz was also youth-driven and represented current culture," says CAA's John Ptak, who worked with Singleton up until his death at 51 in 2019. "Like those films, Boyz helped the studio transition into the modern marketplace."

Indeed, opening in July 1991 against decidedly less edgy offerings like Hot Shots! and Problem Child 2, it ultimately grossed nearly $58 million and scored history-making Academy Award nominations for Singleton, who was the youngest and the first African American nominated for a directing Oscar. (According to a 1996 report in the journal Academic Emergency Medicine, the film may have also contributed to a dip in drive-by shootings in L.A., which fell off sharply between 1991 and 1993.)

In the years since Boyz, Columbia has continued to challenge the status quo. Some releases, like 1992's A League of Their Own and 2023's Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse, proved that more inclusive casting could yield enormous hits; others, like 2010's The Social Network and 2012's Zero Dark Thirty, showed that audiences and Academy members crave more than surface-level insights into contemporary culture.

These days, Columbia's slate, like those of its peers, is largely genre- and IP-driven as it finds itself again at an existential crossroads. "What's gone on behind the scenes has always shaped Columbia," says Galloway. "In a way, [Columbia] is the last of the old studios. It's an era once again when it's risk or die."

Allain knows the paradigm well. After rising to senior vp production, she left Columbia Pictures in 1996 and has produced numerous films by debuting talent, including Craig Brewer's Hustle & Flow (2005), Justin Simien's Dear White People (2014) and Roadside Attractions' upcoming Exhibiting Forgiveness, written and directed by painter Titus Kaphar.

She says that the movies she made with Singleton - and she made four more after Boyz - taught her a key tenet of the business. As she puts it, neatly summing up Columbia's course over the past seven decades, "The singular, auteur voice is the gold standard."

This story first appeared in the July 31 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.