ONE SPANISH REGION WHERE TOURISTS ARE WELCOME – ESPECIALLY SPAGHETTI WESTERN FANS

In the mountains of northern Spain, the sleepy town of Santo Domingo de Silos is accustomed to welcoming pilgrims. In the province of Burgos, on the Camino de Santiago, it is home to one of Spain’s most famous monasteries.

Built in the seventh century, the abbey of Santo Domingo de Silos was catapulted to unlikely stardom in 1994 when its monks had a surprise chart hit with an album of Gregorian chant that sold more than 4 million copies worldwide. The proceeds went towards restoration of the crumbling structure, which was carried out by local builders.

When the world’s gaze moved on, Santo Domingo returned to its sombre life, its hushed streets disturbed only by the toll of the monastery bell and the footsteps of the Camino walkers. So far, so regular a pilgrim’s tale … until 2015, when another grassroots restoration project put Santo Domingo back into the spotlight, and launched a pilgrimage of a different nature.

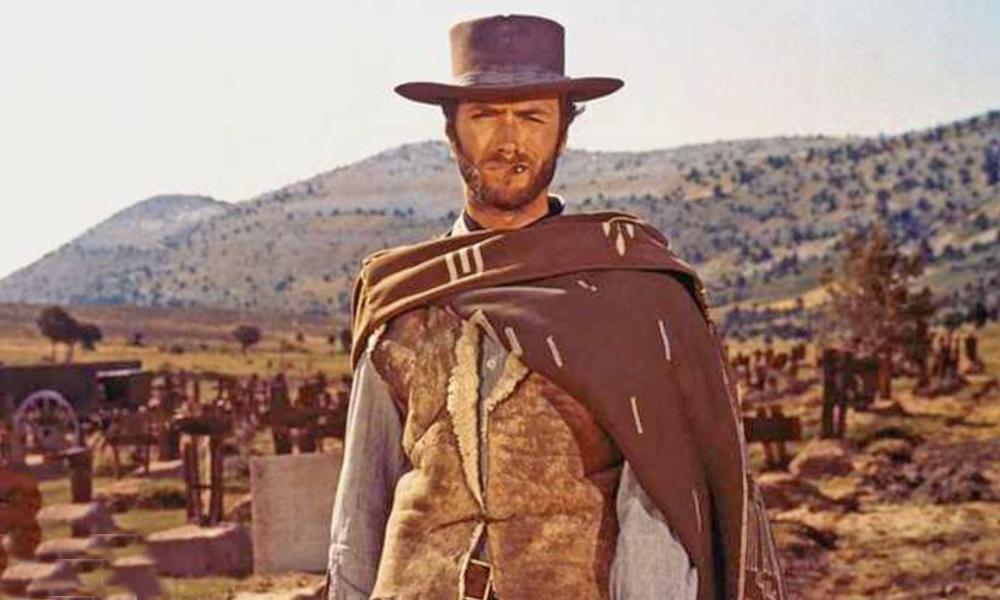

On the edge of town, surrounded by limestone mountains, the long-abandoned Sad Hill cemetery was restored by a local community and a group of enthusiasts from around the world, who spent two years digging it out from under seven inches of earth. However, this is no ordinary cemetery: it contains no corpses and its gravestones are fictitious. It is in fact the film set from the legendary closing scene of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, Sergio Leone’s 1966 masterpiece.

Built for the movie by the Spanish army, the set was abandoned after filming, returned to pasture and ultimately reclaimed by nature. The restoration of its stone plaza, surrounded by 5,000 graves in concentric circles, was an immense feat of determination, devotion and human toil, drawing support from fans including James Hetfield of rock band Metallica, and the film’s leading man, Clint Eastwood. Launched in 2016, and the subject of a Netflix documentary about the restoration, Sad Hill is now firmly on the tourist map, but remains refreshingly uncommercial, something created by fans, for fans.

Related: K-pop tourism: how Tossa de Mar became a hot spot

Now, there’s even more to draw Leone devotees here: the Asociación Cultural Sad Hill has created a new, 21-mile (34km) circular hiking trail, Ruta el Bueno, el Feo y el Malo, connecting the cemetery to three other locations from the film: the Betterville prison camp, near the village of Carazo, the monastery of San Pedro de Arlanza, which represented the Mission of San Antonio, and Arlanza valley, which provided the location for the Battle of Langstone Bridge. As well as an online route map and readily available leaflets, waymarkers decorated with Eastwood’s silhouette make it easy to follow.

The prison camp set and its stockade have been rebuilt using timber from thousands of juniper trees from the nearby Sabinares del Arlanza natural park that were scorched in a 2022 forest fire. The official opening weekend (7-8 September) includes a re-enactment of the battle scene from the film, a musical performance of the Ennio Morricone track from the scene, and a screening of the movie.

It’s easy to see why Leone was so drawn to the region, and how easily it doubles for the American west

I walked a section of the trail on a bright morning earlier this year, and beyond the connection to the film it was a spectacular trek in itself, along rocky tracks through a rugged wilderness with vast, sweeping views. It’s easy to see why Leone was drawn to the region, and how easily it doubles for the American west. Along the trail I came across two diehard fans from France, eagerly surveying the jagged horizon to match it to the appropriate scene on their phone. Location comparison to this level of detail is a big part of the appeal. They went on to reveal that they were staying at the Hotel Nuevo Arlanza in Covarrubias, near Villanueva de Carazo, where the film’s cast and crew were billeted in 1966. Naturally, they’d chosen room number 10, where Eastwood himself had slept.

The success of Sad Hill is a good news story in a region blighted by depopulation. España vacía (empty Spain) is a well-documented phenomenon and a hot political topic. Many villages and towns in the interior are suffering a lack of investment and services, even risking abandonment, as the younger generation move away to seek opportunities in cities and coastal resorts. Meanwhile, in the hotspots of Barcelona, Málaga and San Sebastián, mass tourism is causing housing shortages, high prices and angry protests. It is perhaps unsurprising that the municipal authorities in Burgos, one of Spain’s least populated and untouristy provinces, have embraced the spaghetti western pilgrims with open arms.

The Sad Hill Cultural Association is already planning 60th anniversary celebrations for 2026. However, the film’s connection to the region goes beyond the touristic, having touched many lives, and there’s a strong sense of civic pride about Burgos’s place in cinema history. In Santo Domingo there are still a few old-timers who worked as extras on the shoot, and who tell tales of abandoning their olive-picking duties to take part in the film’s epic battle scene.

Leone’s westerns are enjoying a renaissance – even a rebrand, as demonstrated by a recent season at the BFI, highly collectible reissues of Morricone’s soundtracks and the 2022 award-winning documentary paying homage to Leone’s influence, including contributions from Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino, who cites The Good, the Bad and the Ugly as his favourite film.

The fans I met at the cemetery and on the trail didn’t need the renaissance – they’d been loyal all along. Each had the same wide-eyed look, the same tale of fulfilling a long-held dream, of having finally made it to a place that had loomed so large in their lives. They talked of the first time they saw the movie, how they’d watched it over and over, and the impact of Morricone’s music. One visitor came from Canada to scatter his father’s ashes, fulfilling his last request. Some struck poses and recited dialogue. Others wandered among the “graves”, playing the soundtrack on their phones. What they all did was stand in awe, amazed that they’d really, finally, made it here.

Their motivation mirrors that of the Camino pilgrims – a long and often arduous journey to honour something greater than oneself. The Turkish travel writer Burak Davran hitchhiked his way to Sad Hill, describing himself as a “pilgrim of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly religion” and Sir Christopher Frayling, former chairman of the Arts Council, and Sergio Leone’s biographer, also notes the similarity. Speaking in the documentary, Sad Hill Unearthed, he sums it up: “People want a sacred experience … and they’re not getting it from the church. They’re getting it from art, from film, from pilgrimages of this kind.”

In Santo Domingo, two information boards stand side by side, one for the monastery, one for the cemetery. As Eastwood himself might have said, “There’s two kinds of pilgrims in this world, my friend …” But he might have been surprised to discover just how much they have in common.

Sad Hill cemetery is free to enter. Convento San Francisco has guest doubles from €105. Less pious is Hotel Tres Coronas de Silo (doubles from €100) in an 18th-century building on the main plaza

• This article was amended on 4 September 2024. The original stated that the Monasterio de San Francisco was catapulted to unlikely stardom in 1994 by its monks release of an album of Gregorian chants, whereas it was the abbey of Santo Domingo de Silos.

2024-09-04T06:17:58Z dg43tfdfdgfd